Impeachment as Spectacle — David Masciotra in Salon.

The House Intelligence Committee’s impeachment hearings have been the perfect sweeps-season exhibition of American dysfunction, weirdness and stupidity. Democrats are meticulously proving that President Trump is an inveterate liar who broke the law by transforming international diplomacy into a partisan, tabloid dirt-finding expedition in exactly the buffoonish manner that anyone would expect. Trump is a corrupt con artist unqualified for a junior high student council. Impeachment and removal are beyond debate to anyone of minimal sanity. In other breaking news, the Earth orbits the sun.

More shocking than the extent of Trump’s petty corruption is the obsequiousness of leading Republicans, all of whom have publicly invested in the personality cult surrounding the former host of “Celebrity Apprentice.” Apparently convinced that the country cannot survive without the leadership of the man who had the wisdom to fire Gary Busey in the boardroom, and later defend murderous white supremacists, the GOP have exposed themselves as lacking any of the principles — “family values”; belief in small, honest government; fiscal conservatism, patriotic loyalty to the laws and institutions of the United States — they previously boasted about.

House impeachment, and subsequent Senate removal, in any rational Congress would have taken all of four minutes, allowing the electorate to prepare for the alarming reality of President Mike Pence.

Instead, curious citizens are subjected to the monstrosity of Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, whose previous high-water mark was disregarding accusations of sexual abuse in the Ohio State locker room when he was an assistant wrestling coach, doing his best impersonation of a serious human being as he shouts about “process” in his shirtsleeves. Barring any bombshell, it looks as if the entire Trump fiasco will result in a repetition of the Bill Clinton episode — impeachment in the House, acquittal in the Senate.

That is not the only reason that the entire proceeding feels anticlimactic. It is deeply unsatisfying because it is focused on what is likely the least of Trump’s misdeeds.

At least 25 women have accused Trump of sexual assault – most of them alleging that he forcibly grabbed their genitals, which is precisely what he has bragged about doing on an open mic. Sexual predation and harassment are conspicuously absent from the congressional hearings on Trump, along with media dissection of his presidency. Occasionally, a pundit will casually reference the accusations as if they were nothing more than an unfortunate, but pedestrian reality of national politics. Rep. Katie Hill, a freshman Democrat, resigned over a consensual affair with a staffer, yet Trump faces no political consequences for, according to his credible accusers, a lifetime of assaulting women.

Defenders of the government’s inadequacy in the pursuit of justice might protest that none of Trump’s accusers have alleged any criminal behavior during his presidency. It seems odd that chronology would have any relevance — what if there was evidence that Trump murdered 25 women in the 1990s and 2000s? Would Congress have to ignore it? — but operating only within the confines of Trump’s term in office is equally devastating to not only his lack of leadership and character, but also to an impeachment that, while just and necessary, resembles the prosecution of Al Capone for tax evasion.

The last living Nuremberg prosecutor, Ben Ferencz, called Trump’s family separation policy at the border — ripping children out of their parents’ arms, locking them in cages, leaving them vulnerable to abuse — a “crime against humanity.” Explaining that it was “painful” for him to watch the news of the Trump administration’s cruel treatment of families seeking asylum, Ferencz said, “We list crimes against humanity in the Statute of the International Criminal Court. We have ‘other inhumane acts designed to cause great suffering.’ What could cause more great suffering than what they did in the name of immigration law?”

Ferencz’s outrage barely elicited coverage in the American press, and provoked a pathetically meek political response. The United Nations definition of “genocide,” formed in response to the Nazi holocaust of Jews and other minorities, extends far beyond murder. It also includes “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Genocide is not on the impeachment agenda.

What is on the itinerary, apparently, is a commitment to displaying many American failures of policy and cultural imagination without comment. EU Ambassador Gordon Sondland’s testimony that Trump orchestrated the bribery campaign against Ukraine was damning, but with the exceptions of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, no one appears compelled to discuss why ambassadorial posts are always on sale to the highest donor — a bipartisan tradition that Republicans, as is their wont, elevate to unexplored heights of irresponsibility.

Everyone of conscience should feel grateful to Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman for helping to expose Trump as a criminal who wields presidential power for personal gain, but is it necessary and healthy to celebrate militarism while papering over unjust war?

Yes, Vindman is a lieutenant colonel in the Army. The “service” for which everyone is calling him a “hero” was contributing to one of the most reckless and immoral annihilations of human life in modern history — the illegal invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Meanwhile, in recent weeks Trump has pardoned three accused war criminals.

If by some miracle, the Senate actually convicts President Trump and removes him from office, Americans should applaud in the morning, but go back to protesting by the afternoon. The words that French journalist Claude Julien wrote following Richard Nixon’s resignation still ring true: “The elimination of Mr. Richard Nixon leaves intact all the mechanisms and all the false values which permitted the Watergate scandal.”

Be Nice — Annie Lowrey in The Atlantic on our epidemic of unkindness.

Take five minutes to meditate. Try to quiet the judgmental voice in your head. Call your mother. Pay for someone else’s coffee. Compliment a colleague’s work.

In an age of polarization, xenophobia, inequality, downward mobility, environmental devastation, and climate apocalypse, these kinds of Chicken Soup for the Soul recommendations can feel not just minor, but obtuse. Since when has self-care been a substitute for a secure standard of living? How often are arguments about interpersonal civility a distraction from arguments about power and justice? Why celebrate generosity or worry about niceness when what we need is systemic change?

Those are the arguments I felt predisposed to make when I read about the newly inaugurated Bedari Kindness Institute at UCLA, a think tank devoted to the study and promulgation of that squishy concept. But it turns out there is a sweeping scientific case for kindness. In some ways, modern life has made us unkind. That unkindness has profound personal effects. And if we can build a kinder society, that would make life better for everyone.

Darnell Hunt, the dean of social sciences at UCLA and a scholar of media and race, told me some of the questions the institute hopes to investigate or answer: “What are the implications of kindness? Where does it come from? How can we promote it? What are the relationships between kindness and the way the brain functions? What are the relationships between kindness and the types of social environment in which we find ourselves? Is there such a thing as a kind economy? What would that look like?”

Not like what we have now. Research proves what is obvious to anyone who has been online in the past decade: For all that the internet and social media have connected the world, they have also driven people into political silos, incited violence against minority groups, eroded confidence in public institutions and scientists, and made conspiracy theorists of us all—while making us more selfish, less self-confident, and more socially isolated.

“The internet is largely a cesspool,” Daniel M. T. Fessler, an evolutionary anthropologist and the new institute’s director, told me. “It is not actually surprising that it is largely a cesspool. Because if there’s one thing that we know, it’s that anonymity invites antisociality.” It is easier to be a jerk when you are hiding behind a Twitter egg or a gaming handle, he explained.

The political situation is not helping matters, either. Americans have become more atomized by education, income, and political leanings. That polarization has meant sharply increased antipathy toward people with different beliefs. “We’re in this hyperpolarized environment where there’s very little conversation across perspectives,” Hunt said. “There’s very little agreement on what the facts are.”

There’s plenty of pressure for people to be unkind to themselves, too. Matthew C. Harris and his wife, Jennifer, seeded the Bedari Kindness Institute with a $20 million gift from their family foundation. For him, the topic is personal. “I wasn’t kind to myself, which has roots in my own childhood experiences. I was judgmental of myself, and therefore others. I was very perfectionistic,” he told me, reflecting on his business career. “I realized: This is not sustainable.”

The antidote seems to lie in media, economic, social, and political change—lower inequality, greater social cohesion, less stress among families, anti-racist government policy. But kindness, meaning “the feelings and beliefs that underlie actions intended to generate a benefit for another,” Fessler said, might figure in too. “Kindness is an end unto itself,” and one with spillover effects.

At a personal level, there’s ample evidence that being aware of your emotions and generous to yourself improves your physical and mental health, as well as your relationships with others. One study found that mindfulness practices aided the caretakers of people with dementia, for instance; another showed that they help little kids improve their executive function.

Kindness and its cousins—altruism, generosity, and so on—has societal effects as well. Fessler’s research has indicated that kindness is contagious. In one major forthcoming study, he and his colleagues showed some people a video of a person helping his neighbors, while others were shown a video of a person doing parkour. All the study participants were then given some money in return for taking part, and told they could put as much as they wanted in an envelope for charity. (The researchers could not see whether the participants put money in or how much they put in.)

People who saw the neighborly video were much more generous. “One of my research assistants said: ‘There’s something wrong with our accounting; something’s going haywire,’” Fessler told me. “She said, ‘Well, some of these envelopes have more than $5 in them.’” People who saw the first video were taking money out of their own wallets to give to charity, they figured. “I said, ‘That’s not something going wrong! That’s the experiment going right!’” It suggests that families or even whole communities could pitch themselves into a kind of virtuous cycle of generosity and do-gooding, and that people could be prompted to do good for their communities even with no expectation of their kind acts redounding to their own benefit.

Interpersonal empathy might translate into political change, Hunt added. “We see this [research] as being civically very important,” he said. “Take homelessness in L.A., for example. How do we get the electorate to become more empathetic and support policies necessary to make a meaningful intervention? That’s not something you can just do by fiat. People have to be brought along.”

This holiday season, there are so many ways to bring yourself and your community along—among them little things like taking five minutes to meditate, calling your mother, and paying for someone else’s coffee. Maybe kindness is not a distraction from or orthogonal to change. Maybe it is a pathway to it.

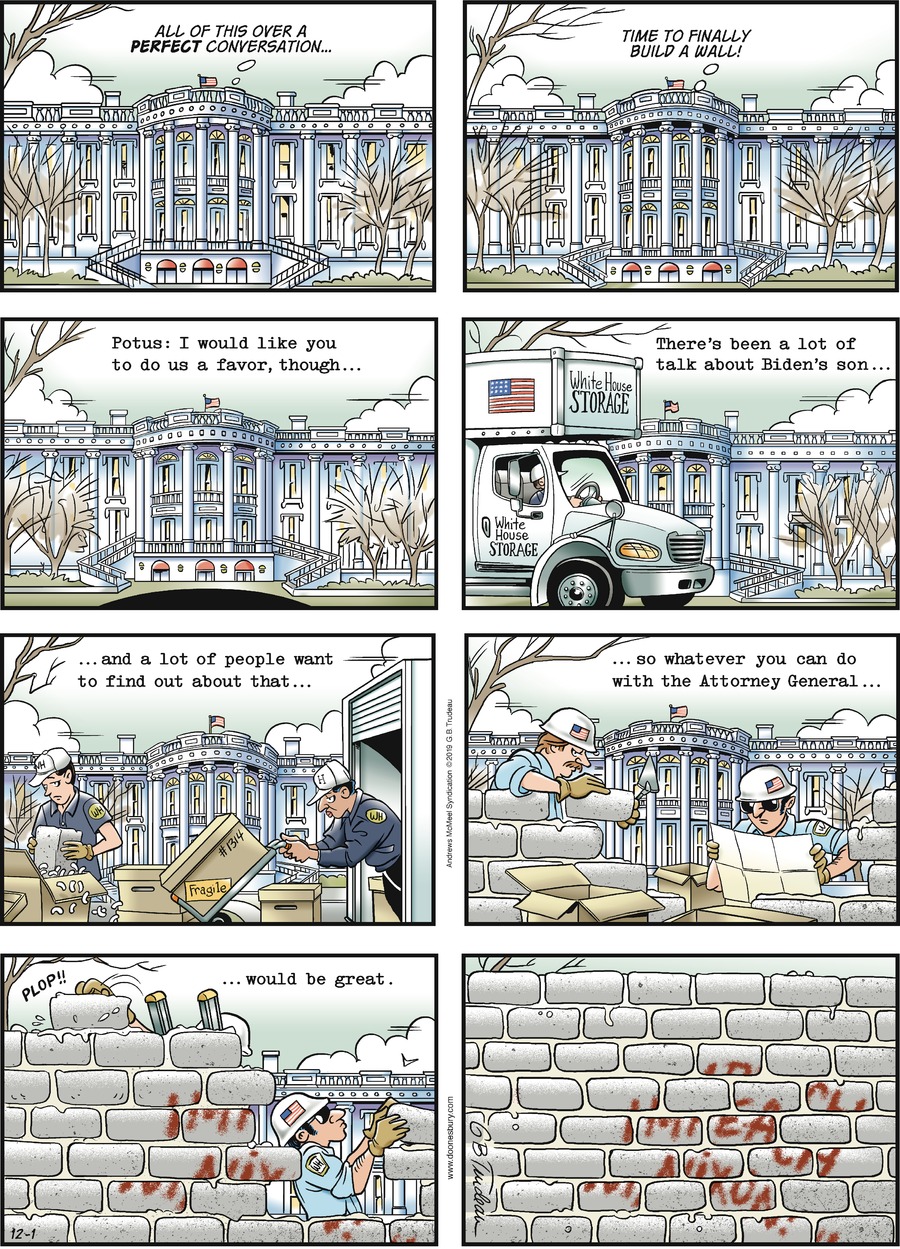

Doonesbury — Remember the wall.